Judges who have been stripped of their judicial powers

Assessments from the European Court of Human Rights

"What is it that makes us trust our judges?" - This question was asked by one of the most influential judges in US history, John Marshall, and he answered: "It is the independence they have in the exercise of their powers and how they are appointed."

In a country that is still a long way from the American standard of justice, we ask the question: What is it that makes us distrust our judges? If we apply the opposite premise to the logic of Judge Marshall's thesis, the determinant of the public's lack of trust in the judicial system should be the lack of guarantees for the way judges are elected and in the independence of their activities.

We will check the validity of this answer concerning Georgian justice, based on the judgments of the European Court against Georgia: in the article, we will tell you about eleven judges who were refused to exercise their judicial powers and were deprived of the opportunity to defend their right to a "fair court" provided by the European Convention.

Selection of judges:

"I choose, you choose not!"

The 2012 Dublin Declaration, adopted by the European Network of Justice Councils, stated that 'the entire process of selection and appointment of judges should be open to public scrutiny, as the public has a right to know how its judges have been selected.' (1) The Venice Commission has expressed the opinion (2) that "reasoned decisions on the selection and exclusion of candidates should be presented, with the possibility of appeal in court." The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe encourages countries to make available the reasons for selection or rejection, as well as the possibility of appeal or at least the procedure by which the decision was made. (3) The spirit of this and a number of other international instruments on the appointment of judges is to minimize the risk that the decision-maker will subjectively choose only what „their heart desires.”

The case of Marina Glovel

Marina Gloveli, (4) a former judge of the Tbilisi Court of Appeal and a lawyer with twenty years of professional experience, tried five times in 2015-2017 to occupy the vacant position of a judge and, each time, unsuccessfully. In 2017, she took part in the competition for the sixth time and was informed that her application was rejected. Glovel appealed this decision to the qualification chamber of the Supreme Court as biased. The qualification chamber recognized Glovel's appeal as inadmissible. They explained that they could not discuss this matter, because the candidate, due to the minimum points accumulated in the competence part, was excluded from the competition, so the decision to refuse her appointment was not made by the Supreme Council of Justice.

The case was that the Chamber relied on Article 36(4) of the Organic Law of Georgia "On General Courts", Clause 13, according to which, if a candidate fails to score 70 percent of the maximum number of points in the competence or integrity section, the Supreme Council of Justice will not put their candidacy to the vote. In this regard, only the Chairman of the Council issues a legal act, and it can be appealed only in a conspicuously formal way: in the same body - the Council.

In a different situation are those candidates who successfully pass this stage and then refuse to be appointed. They can appeal to the Qualifications Chamber of the Supreme Court and challenge the bias, discriminatory nature of the evaluation process, use of false information, abuse of power, and procedural violations.

The European Court of Human Rights evaluated the refusal of the qualification chamber to consider Glovel's complaint. They pointed to the evidence - the statement of the non-judge member of the Supreme Council of Justice, Nazi Janezashvili, that the council arbitrarily lowered the scores of other candidates to provide its "protégés" with favorable conditions. (5)

The European Court drew attention to the fact that the former judge was selected based on an application, then evaluated her "background", the members of the Council conducted interviews with her and finally made a conclusion regarding her integrity and competence. The court emphasized that all the competitive stages passed by the applicant were carried out by the Supreme Council of Justice, and determined:

"The Qualification Chamber did not take into account the position of the Constitutional Court of Georgia, according to which the constitutional right to a reasoned decision meant the presentation of adequate reasons throughout the appointment process, and since the appointment of judges is the constitutional authority of the Council, the right to a fair trial includes the requirement that all decisions (acts) of public authorities that Violate human rights to be appealed and reviewed by the court.''(6)

"By absolving itself of jurisdiction to hear the applicant's appeal against the Board's decision, the Qualifications Chamber violated the very essence of the applicant's right of access to a court." The state was ordered to pay 3,600 euros in favor of the applicant. (7)

Based on the decision of the European Court in the case of Marina Gloveli, the Georgian Court Watch believes that it is appropriate to amend the Organic Law of Georgia "On General Courts" to appeal the evaluation process in the Qualification Chamber of the Supreme Court an available mechanism for candidates for the position of a judge who failed to pass the points.

The case of Maya Bakradze

This time, the European Court is considering the case of another former judge of Georgia - Maya Bakradze. Bakradze, who had been a judge of the Tbilisi Court of Appeal for ten years, was no longer appointed to the position of a judge by the Supreme Council of Justice. Mrs. Bakradze claims that she is being punished for critical opinions expressed towards the Council within the framework of the membership of the association "Union of Judges of Georgia". Currently, in this case, the stage of exchange of information and evidence is underway, and soon the final assessment of the European Court will see the light of day.

Disciplinary responsibility is like a sword on the judge's head

"The accountability of the court collides with independence - the foundation of the rule of law. ... Disciplinary responsibility is the most controversial form of accountability, given its relationship to judicial independence. Judicial discipline can be used as a destructive tool to reduce the impact of individual judicial decisions by discrediting those who made them. The disciplinary regime consists of a series of rules that make judges accountable for serious forms of misconduct and thus contribute to increasing public confidence in the courts. However, first of all, there should be sufficient protection mechanisms so that it does not undermine the independence of the court.''(8)

The case of Mitrofane Sturua

Mitrofane Sturua (9) was the chairman of the Abashi district court. In 2004, the Supreme Council of Justice of Georgia started disciplinary proceedings against him. They disputed the delay of the criminal case materials for six months after the case was removed from consideration. Sturua admitted that he committed the said act through negligence. The Disciplinary Board, after the oral hearing, found him guilty of disciplinary misconduct - "unreasonable delay in the consideration of the case, failure to fulfill the duties of a judge or improper performance, or any other violation of labor discipline"; As a result, he was dismissed from his position.

Sturua appealed the decision to the Disciplinary Council of Judges. The latter considered the appeal at a plenary session with eight judges. Of these, four judges - K. K., G.C., D.S., and T.T. Previously, participated in the consideration of this case by the disciplinary board. Among them, K.K. Both in the first instance and at the stage of consideration of the complaint, he acted as the chairperson and speaker of the session. The Disciplinary Council unanimously agreed with the decision of the panel.

The applicant appealed the legality of the composition of the disciplinary body and also the fact that he was not invited to the relevant session in the Supreme Court. His complaint was not accepted in the proceedings due to lack of justification.

Sturua continued the dispute in the European Court. The latter concluded that, contrary to the requirements of the right to a fair trial, the same four judges reviewed their judgment and assessed whether they had made an error in their assessment of the facts or in their interpretation of the law.

However, since the Supreme Court's role was limited to assessing the legal aspects of the case, the European Court could not be convinced that the cassation instance had the power to review the case effectively. Finally, it found that the applicant's fears about the bias of the Disciplinary Board were objectively justified.

The government of Georgia was ordered to pay 3,500 euros to the applicant for the violation of the right to a fair trial, and 3,380 euros for reimbursement of other expenses.

Based on the decision of the European Court, Judge Sturua appealed to the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court on July 3, 2017, requesting the annulment of the decision on his dismissal. The Disciplinary Chamber annulled the decisions of the Disciplinary Panel and the Disciplinary Council and sent the case back to the Disciplinary Panel for reconsideration. According to the decision of the Disciplinary Board of September 25, 2017, the disciplinary proceedings were terminated because the statute of limitations for committing a disciplinary offense had expired. Nevertheless, Judge Sturua appealed to the Supreme Council of Justice and requested to be reinstated to the position of judge and to receive a provisional salary. The council did not meet his demands.

The case of Zurab Gabaidze

The applicant Zurab Gabaidze (10) was a judge of the Khulo District Court. In 2004, the disciplinary panel found him guilty of disciplinary misconduct - "gross violation of the law"; He was accused of leaving the convict in illegal detention for fourteen days. Despite the good professional reputation of the applicant and the absence of disciplinary action against him in the past, Gabaidze was dismissed from his position. He appealed the decision to the disciplinary council. The latter upheld the decision of the disciplinary board. The applicant appealed to the Supreme Court, which annulled the decision of the Disciplinary Board due to insufficient legal reasoning and remanded the case for reconsideration. The Disciplinary Board reviewed the case again and made the same decision. Three members of the panel of judges - .K. K., G.C, and I. Q. also participated in the first review of this case by the Disciplinary Council. On this basis, the applicant requested their dismissal, but to no avail.

Gabaidze again appealed to the Supreme Court on the basis that his case was considered by an illegal composition in an accelerated manner. This time, the Supreme Court determined that the case was thoroughly discussed and the punishment was adequately determined; Also, the composition of the disciplinary body reviewing the applicant's case was legal; The fact that individual judges had previously participated in the consideration of the applicant's case was in accordance with the practice established based on the law and did not raise questions regarding their impartiality. The applicant appealed to the European Court.

The European Court noted that it had already assessed the legality of the composition of this specific disciplinary body in the Sturua case, once again repeated the reasoning developed in the said decision and this time found a violation of the first paragraph of Article 6 of the Convention.

The country was ordered to pay 3,500 euros in favor of the judge, and 2,140 euros to cover court costs.

Based on this decision, Gabaidze went through the same legal path to be reinstated as a judge as Mr. Sturua from the Disciplinary Chamber of the Supreme Court to the High Council of Justice, but with no results just like him.

Disciplinary measures as a tool of repression

The Bangalore principles of the conduct of judges establish: "A judge must perform his judicial function independently, based only on the assessment of facts, by an independent understanding of the law..." International standards on disciplinary proceedings are imperative, non-interference in the judge's judicial activities, and due to the interpretation of the legal norm, the judge's Inadmissibility of disciplinary responsibility.

The case of Merab Turava, Nino Gvenetadze, Murman Isaev, and Tamar Laliashvili

On September 19, 2005, the Supreme Council of Justice initiated disciplinary proceedings against Supreme Court judges Nino Gvenetadze, Merab Turava, Tamar Laliashvili, and Murman Isaev (11). The official basis of the proceedings was the incorrect interpretation of legal norms by the judges when considering specific criminal cases.

The initiator of the process was the then chairman of the Supreme Court. The law gave him the authority to single-handedly decide to initiate disciplinary proceedings, collect the relevant evidence and then assess it himself as the chairperson of the disciplinary body.

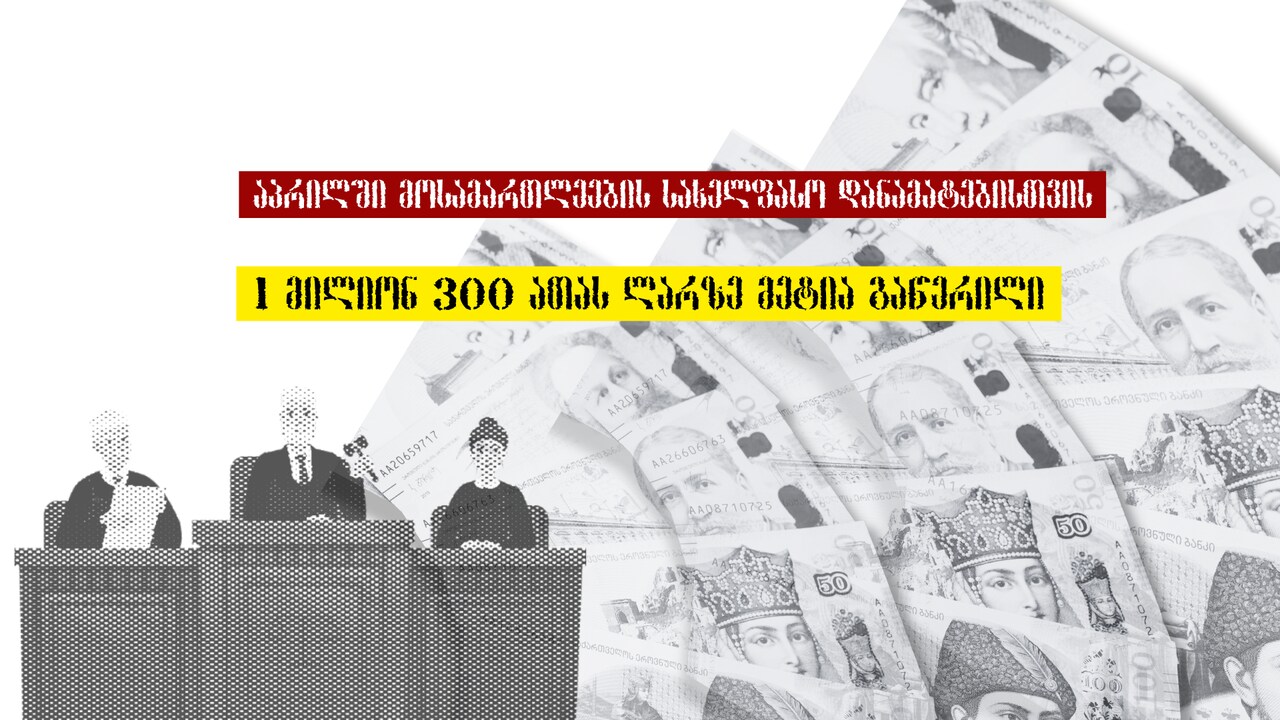

The disciplinary board applied the most severe measure among disciplinary punishments - dismissal of judges.

The dismissal of the judges of the Supreme Court caused a wide resonance in Georgia and became the focus of the attention of the international community. The former judges appealed the case to the European Court of Justice, and the final ruling on the case was highly anticipated in the legal professional community. However, in March 2015, the former judge of the Supreme Court, Nino Gvenetadze, was appointed as the chairman of the Supreme Court, and in April 2016, she refused to continue the consideration of the appeal. Another former judge, Merab Turava, did the same in the same year, because he was appointed as a judge and then chairman of the Constitutional Court.

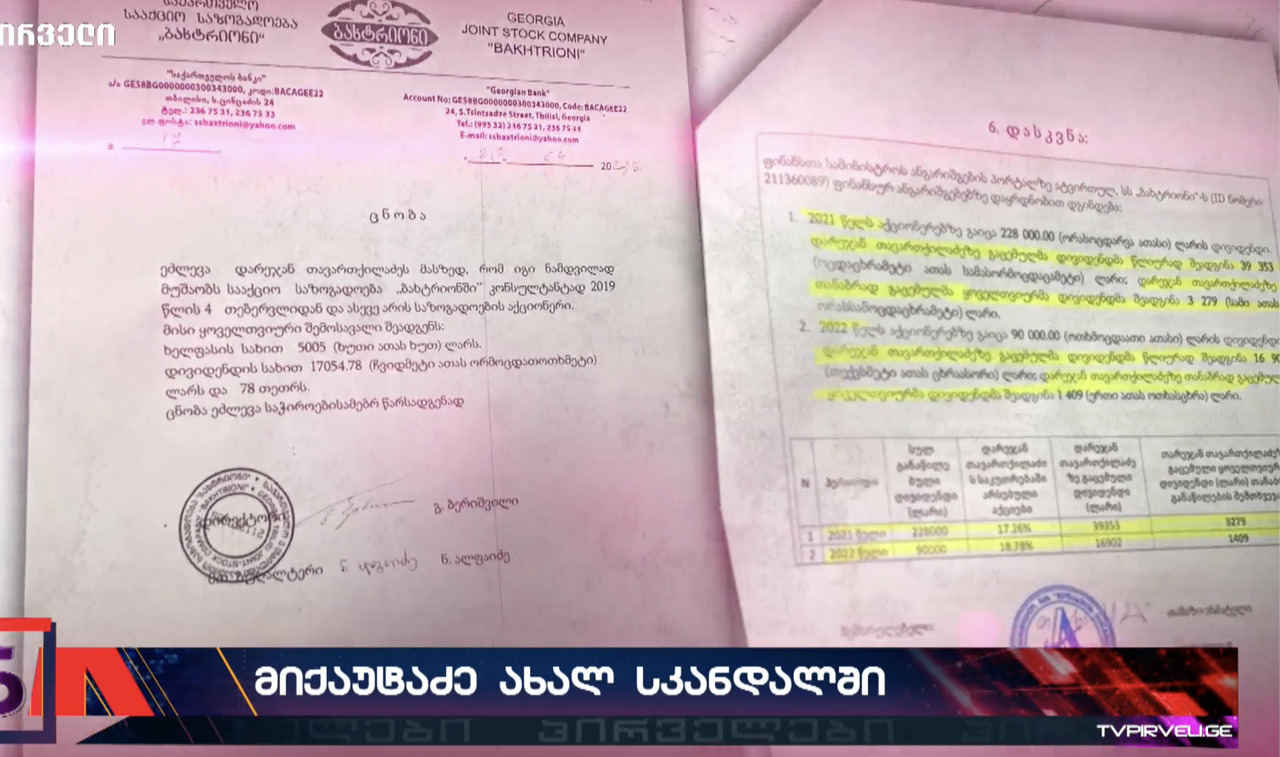

To the other applicants - Murman Isaev and Tamar Laliashvili, the government of Georgia paid 10,000 euros to each of them as part of the settlement, to compensate them for material and non-material damages. In addition, in 2017, Isaev was appointed to the Tbilisi Court of Appeal of the Supreme Council of Justice for life, and 2 years later, he ended his term of office due to reaching retirement age.

The cases of Tamaz Iliashvili, Nunu Alasania, and Levan Bardavelidze

The cases of the Supreme Court of our country and other judges were also transferred to the European Court of Human Rights for consideration. (12) Similarly, they were dismissed from their positions on the grounds of committing a disciplinary violation - a misinterpretation of a legal norm. The new government acknowledged the violation of the right to a fair trial by the previous government, resulting in a total payment of 13,000 euros in favor of the applicants.

"The existence of the judicial system in the state is based on the trust of the society" 13

As a result of the fourth wave of judicial reform implemented in 2018, the grounds of disciplinary responsibility were reshaped, and each of the misconducts that were used as a basis for the prosecution of judges in the cases described above have been removed or modified today. However, the lever for conducting the disciplinary proceedings is still in the hands of the High Council of Justice, and there are no procedural safeguards to protect the judge from its abuse.

A review of the judgments of the European Court revealed that the process of selection and appointment of judges does not meet the requirement of impartiality; And even if a judge successfully navigates this process, he remains vulnerable to the unbalanced power of the governing body.

Depriving the judge of the right to adjudicate in each individual case is unacceptable, as is the injustice that the individual suffers when confronting the system; Even more alarming, however, is the effect such cases have on the judges who remain in the system: these precedents undermine our trust in them; However, justice that is not based on public trust does not exist.

Note:

- The Minimum Rules for the Selection, Appointment, and Promotion of Judges were adopted by the General Assembly of the European Councils of Justice in May 2012.

- Urgent Opinion on the Election and Appointment of Judges of the Supreme Court adopted by the Venice Commission, at its 119th Plenary Session, June 21-22, 2019.

- Recommendation CM Rec (2010)12 of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe to Member States on the independence, effectiveness, and responsibilities of judges, adopted in November 2010.

- Glovel v. Georgia, no. 18952/18, April 7, 2022.

- The same, paragraph 11.

- The same, paragraph 58.

- The same, paragraph 59.

- Judging the judiciary, Responding to Judicial misconduct without threatening independence, Morgane Coué • Mélanie Vianney-Liaud, France

- Sturua v. Georgia, 45729/05, 28.03.2017.

- Gabaidze v. Georgia, 13723/06, 12.10.2017.

- Turava and others v. Georgia, Laliashvili v. Georgia, no. 7607/07 და 8710/07, 27.11.2018.

- Iliashvili v. Georgia; 22715/07, 9.10.2018; Alasania and Bardavelidze v. Georgia, 12611/08 and 25500/08, 9.10.2018.

- Bangalore Principles of Judicial Conduct, Preamble, July 2006.

---

The materials distributed by courtwatch.ge and published on the website are the property of "Georgian Court Watch", when using them, "Georgian Court Watch" should be indicated as the source.